Mai Hữu Liên is 79. Slight, dapper and sprightly he rises from the floor as though still a boy. He lives in a house built 22 years ago and which is just a few hundred yards from the place of his birth in the village of Quang Trung, near the town of Tĩnh Gia in Thanh Hóa Province, which remains one of the poorest areas of Vietnam. He had one elder sister and 11 younger siblings, and himself has four children and 9 grandchildren.

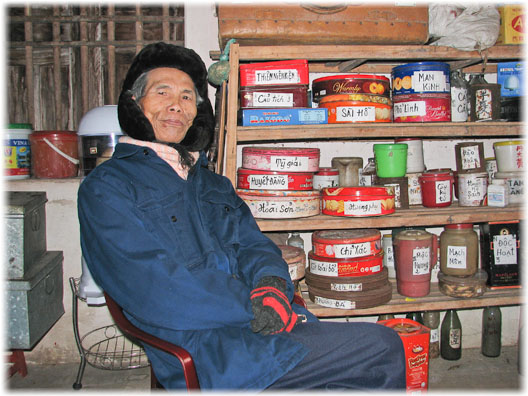

Mai Hữu Liên by his store of medical supplies in his house in Thanh Hóa Province

|

After his first wife’s death he remarried a forty-something at the age of 75. While he may not have moved far, the world around him has revolved at alarming speed. The baby of three generations ago entered one of the most prosperous families in a poor village, the prosperity was based on learning in Chinese and in Nom (the old Vietnamese written system) and in the application of the knowledge so gained to the art of Chinese Medicine which they practiced locally. Much of the established order, of which they were part, with its roots back through the millennia-old Confucian system, had survived under the French occupation, but has since been swept away with independence, the American War and the last 30 years of peace. In his part of Vietnam, that French occupation was hardly noticeable, at his birth the French had been there less than half a century, and the only French people in the vicinity were the Catholic priests at two churches both some miles away.

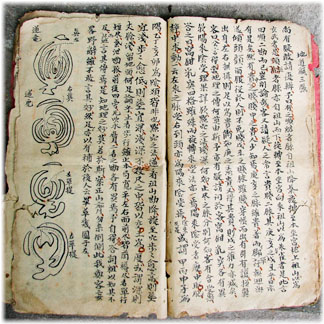

A page from Liên’s father’s hand written book of auspicious advice

|

He started learning the ancient family arts from his father when he was 12. He learnt with the help of books beautifully hand written in Chinese by his grandfather, and from old printed Chinese texts, and expected that his life would continue as lives there had been for generations. From the age of 10 he also attended a school which offered 7 years of classes to the village children. The wider world at this time was fast changing. On the northern border of Vietnam, Hồ Chí Minh was just entering the country to lead the final uprising against the French, with the ensuing declaration of independence four years later in 1945. The Japanese took control of the country, and then, at the same time as the resulting political chaos, there were disastrous storms in the October of 1944. These were so bad that he remembers 19 of their 20 rice stores being destroyed, together with all the standing crops. The resulting widespread famine lasted for 6 months across Vietnam, and in that time almost half of the population of his village died of starvation. He recalls with visible pain the bodies of the dead he saw on the way to school, the burial pits, and the finding of decomposed corpses. Many of his friends died.

The following years, after independence had been declared, were dominated by the continued war with the French during which time Liên worked in a local government office and then as a teacher. This stood him in bad stead for what was to follow, for although he was not connected with the colonial French administration from earlier years, he was, like his fellow teachers, to be seen as part of the elite class who had been richer than those around them.

A magnetic device to aid house lay-out

|

When the French were defeated after nine years of struggle there was an understandable euphoria, the people under occupation had seen systematic and widespread abuses with indentured labour and physical punishment from employers. These employers were usually the richer Vietnamese within the community and rather naturally excesses against them followed the French withdrawal.

These excesses were soon, if a little belatedly, acknowledged by President Hồ Chí Minh and brought to an end. But in the months of that uncharacteristic delay, government special committees went round the country systematically identifying undesirable elements; roughly anyone who had had any money before independence, and stripping them of all property and assets. While the idea of re-distribution was in accord with the new legal system, and intended to aid the poorer members of the community, the effect was to sanction victimisation of some individuals who were illegally executed, and promote the destruction of property which served only the need for retribution. Liên recalls no such killings locally as he says everyone was simply too poor to be singled out, but his family had two houses which were confiscated together with all their stock and food so that he and his brothers had to collect shell-fish to sell in order to buy rice to eat. However, what seems to make him saddest was the wonton destruction of many of the family’s old books, which were simply burned. He and other teachers, including one of his younger brothers, then had to stop teaching and to work in service in return only for their food. He remembers trying to take some growing rice for his family and being ‘arrested’ and confined by local farmers for his pains. He identifies it as the most difficult period of his outwardly difficult life.

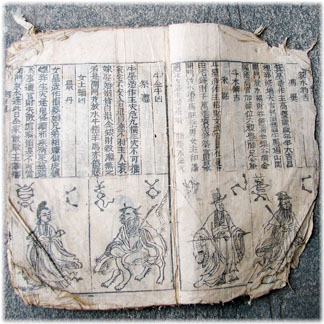

A page from a prognostication almanac

|

Now Vietnam was facing a new threat, the Japanese, Koreans, British, Chinese and French having been evicted it was the turn of the Americans to take an unwanted interest. This part of Thanh Hóa is dominated by the main Hà Nội to Hồ Chí Minh road, ‘Highway 1’, which was a key target of the American bombing in the coming years. Liên worked as a teacher throughout this period, that is between the bombing from planes in the day time and the shelling from ships at night, and recalls the air raid shelters they dug and used. The village saw fortunately few deaths, these being restricted to a handful of families who were not able to get out of their houses before their properties were raised by the enemy fire. But there were many civilian casualties near the main road bridge at the Province capital, 25 miles to the north.

During the American War there was enough to eat. Land had been nationalised and farmers were paid in food according to the days they worked, members of the forces, teachers and other public servants were similarly paid. When Vietnam finally was allowed to live in peace with itself at the end of the war he was nearing retirement and in 1978 gave up teaching with testimonies from the government in gratitude for 30 years of service to his country as a teacher throughout the long history of troubles. The government was appreciative of all its workers by that time, but an interesting codicil is the fact that although he had applied for Party Membership from the time when teachers were again acceptable, he had not been allowed to join. His younger brother Hoàn, also a teacher, had been able to enter the army, (there being a minimum weight restriction which had prevented Liên’s entry), and soon was in the Party.

At the age of 59 Liên was finally able to devote himself to what he considered to be his proper vocation: helping people in the community with his knowledge of Chinese Medicine and the understanding of life’s vicissitudes that goes with it. This story has been a political sketch that says too little about the man, but that reflects an imbalance between his personal aspirations and his actual life, and this implicitly tells us of something more fundamental, for this is a society which sees individuals as parts of an important whole, rather than the whole as made up of important individuals.

Go to the previous 'most recently added page'