|

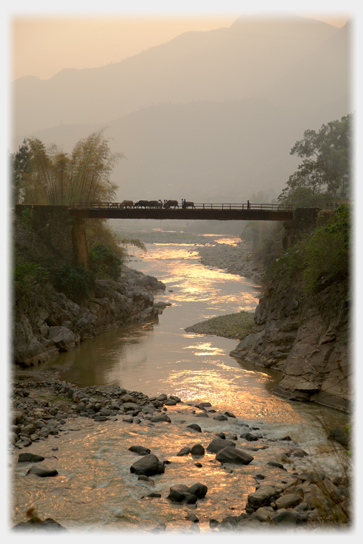

Getting There

How estimable–a slow pace of life which allows the return at the end of the day to be at the pace of the buffalo. But hardly relevant to those of us who must get to work, feel pressured to perform, or just don't like being on this motorway. We all hurry sometimes; the young herders on the bridge will run for cover if a tropical downpour approaches, we hardly loiter on Edinburgh's North Bridge if an east wind is blowing. However, such haste is specific and exceptional.

The problem is when rush becomes the norm; then we seem to be perpetually in the wrong place, and are trying to be in another place. Maybe if this is always true of ourselves we need to ask how it can be that we are forever half an hour behind–can we not reset our mental clocks every six months just as we reset to summer time? No, because the rush is a concomitant of something more fundamental–anxiety; rushing not only makes us anxious, but arises out of our anxiety.

Our anxiety comes from a deep need to forestall anticipated problems; indeed this is a very deep need, for it lies at the root of consciousness. A key aspect of the work of consciousness is to create a kind of personal 'model' of the world in which we live, one with the extraordinary and possibly unique property of allowing us a picture of what may happen next; it lays out a map of the future, and by examining it we can prepare ourselves for what may come; we can attend to problems before they happen.

The sting in the tale of this wonderful ability is that we may become so absorbed negotiating with ourselves over minutiae, worrying over matters which may or may not a arise, that we quite forget about the present. Our lives are invaded by unnecessary worries. One consequence of this is the massive use of drugs aimed at anxiety reduction: at reducing the hyperactivity of our internal 'planning department', to this end alcohol is perfectly suited. But the worries return despite the drugs. What is striking is the contrast in our reactions to these usually trivial worries, and our reaction to major events. When the infrequent big problems of life do face us, we often find that minimal thought and minimal mental effort are all that is required.

Anxiety seems to come in hand with urbanisation. Recent years have seen a massive shift of populations leaving behind the bucolic life exemplified in the picture, and taking on the stresses of urban living; a movement to which our modern mega-cities testify. The scale of this movement, and resulting distress, is now great, but the pattern of movement to urban centres, and then the resulting need to escape urbanity, is not. Classical Chinese abounds with poets repining for lost halcyon days. Poets such as Tu Fu lament the sorrows urban life produces; and even earlier, 1,600 years ago, the good fortune of escaping the stress of urban life and returning to the country is here celebrated by T'ao Ch'ien (Hinton, 2008).

Home Again Among Fields and Gardens...I stumbled into their net of dust, that one departure a blunder lasting thirteen years. But a tethered bird longs for its old forest and a pond fish its deep water–so now, my southern outlands cleared, I nurture simplicity among these fields and gardens, home again....

Anxiety is no new invention, nor is its counterpart, the dream of slowing down.

References

- Hinton, David (2008, translation) 'Classical Chinese Poetry' Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York. Includes poems by T'ao Ch'ien (365-427)

8th July 2015 ~ 5th September 2015