|

On Nature

Born - the window of experience opens onto a fresh, uncluttered world. The slate awaits experience, maybe a mind, to write on it. Our word 'nature' comes from the Latin natura signifying birth - as in nascent - but the Roman meaning, just like ours, does not stop at that event. It flows on through life, being the course of things, their very constitution, their character. Here we can see the blossoming of our world as it opens up.

It is because it takes us from birth, through essence, through form, to encompass the whole mature individual person or thing, that nature is such a potent word. The constitution, the essential character of the subject, is there from its birth, waiting ready to burgeon or implode. We speak of the nature we knew he had, how it was in his nature. Nature traces that course from its seed to its fulfilment.

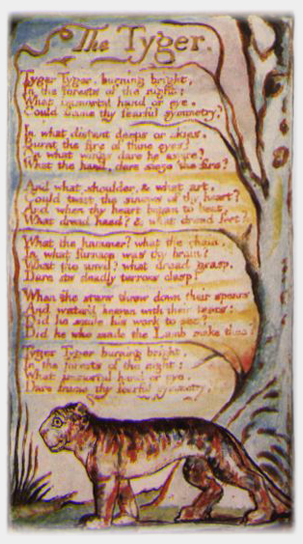

But the word's common use is far from confined to individuals, rather nature is our 'environment' - to use the vogue term. It is that in which we find ourselves, although it is that part which is not made by us. So we can escape from the manmade world into it. We return to nature, maybe even slipping off our clothes to be naturalists and so nearer to our nature - seeking our pre-civilised state; and then almost at once we want to re-capture nature, to take her back to civilisation by photographing or painting it - as in the picture above. Here the word nature stands over and against human conception and construction.

And then finally the word comes to embrace even that very wrought world. Now we have the totality of nature: all that is out there, everything that is not mental. This is Collingwood's concept in his 'The Idea of Nature' where the word is taken as being akin to cosmology: now nature is the entirety of the world or universe.

Our fecund modern word emerges. Brimming with meanings, overflowing with connotations; a rich vein for poetry and a great head-word to which we are easily drawn. Drawn not only by the way it seems to open up a whole new world, but by the way that world is both familiar and at the same time

independent.

This seems crucial, nature's permanent independence sets it apart from human beings. That independence allows it to become a world on which we can depend; it is available whether or not we are there, whether or not we observe it, whether or not we attend to it. It is so familiar that we may give Nature a capital N, and those of us who would be shy of deifying, still fondly personify, and speak of 'her'. But at the same time she is so independent that it is her

tigers

that eat those lambs ... and then they eat us ... and so bring to an end the

world

of our thought ... reaffirming the boundary between the mental and nature, lest we might have thought tygers, as all God's creations, to be safely caged.

that eat those lambs ... and then they eat us ... and so bring to an end the

world

of our thought ... reaffirming the boundary between the mental and nature, lest we might have thought tygers, as all God's creations, to be safely caged.

The illustration Blake drew for his poem has such a sweet domestic cat that the 'darkness' is hard to believe. Notwithstanding the illustration traditionally the tyger is taken as a symbol of the devil's work. For us this needs translating. Without a supporting God, what happens when we find that it is we who created tygers?

References

- Collingwood, R. G. (1945) 'The Idea of Nature' OUP (p. 1)

12th May 2015 ~ 28th July 2015